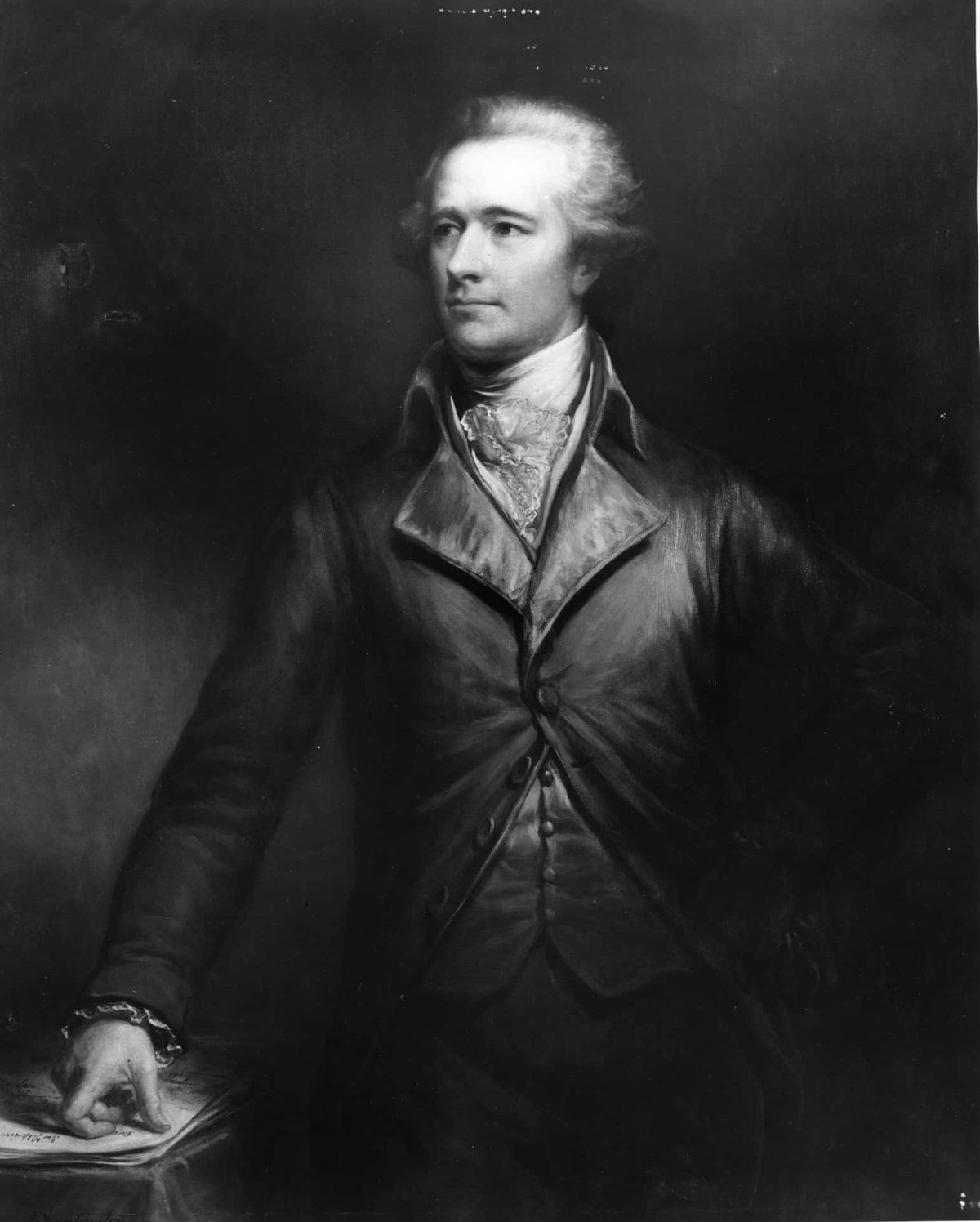

The relationship with Alexander Hamilton that most dramatically shaped the nascent American republic wasn't a romance, but a political clash of epic proportions: his fierce rivalry with Thomas Jefferson. Their deeply antagonistic, yet sometimes pragmatic, dynamic became the crucible in which America's foundational political ideologies were forged. But Hamilton's life was also marked by other significant bonds, including an intense, historically debated friendship with John Laurens and, of course, the enduring ties of family.

Understanding Hamilton's various relationships isn't just about historical curiosity; it’s about peeling back the layers of personality and principle that underpinned the creation of the United States. It's about recognizing how ambition, ideology, and human connection intertwined to determine the course of a nation.

At a Glance: Hamilton's Key Relationships

- Thomas Jefferson: His primary political antagonist. Their conflict over government power, economic policy, and national vision defined America's early years.

- John Laurens: A close, deeply affectionate friendship that has sparked modern speculation about its romantic nature, though historical context suggests strong platonic bonds common in the era.

- George Washington: His mentor, commander, and the figure whose trust Hamilton largely retained throughout his career.

- Aaron Burr: The ultimate rival whose fatal duel brought Hamilton's life to an abrupt end.

- Eliza Schuyler Hamilton: His devoted wife and the anchor of his personal life, who outlived him by 50 years.

The Genesis of a National Divide: Hamilton vs. Jefferson

Imagine two intellectual heavyweights, both brilliant, both passionate, both convinced they held the key to America's future, yet standing on fundamentally opposite sides of every major issue. That was the essence of the relationship between Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson. Their conflict wasn't mere personal animosity; it was a profound ideological struggle over the very soul of the young United States.

It all began when both men joined George Washington’s inaugural cabinet. Hamilton, as Secretary of the Treasury, envisioned a powerful, centralized federal government fueled by commerce, industry, and robust financial institutions. He saw cities as the engines of wealth and progress. Jefferson, on the other hand, served as Secretary of State and harbored a deep distrust of centralized power, viewing it as a gateway to tyranny. He championed an agrarian republic, believing a nation of independent farmers was the bulwark of liberty, famously dismissing cities as "great sores" on the body politic.

These differing worldviews set the stage for a conflict that would define America's first decade.

The Battle Over the National Bank: A Core Contention

Hamilton’s ambitious financial plan was the primary flashpoint in his evolving relationship with Jefferson. At its heart was the proposal for a national bank. For Hamilton, this bank was essential to stabilize the nation's finances, consolidate war debts, and foster economic growth. He saw it as a necessary instrument for a strong nation.

Jefferson, however, viewed the national bank with profound suspicion. To him, it represented a dangerous concentration of power, a replication of the "evils" of European monarchies and financial systems that threatened his vision of a decentralized, agrarian republic. He believed such an institution exceeded the federal government's constitutional authority, advocating for a strict interpretation of the Constitution.

On February 15, 1791, Jefferson formally expressed his constitutional concerns to President Washington, urging a presidential veto of the bank bill. Hamilton, in turn, masterfully articulated his doctrine of "implied powers," arguing that the Constitution granted Congress powers beyond those explicitly enumerated, so long as they were "necessary and proper" for carrying out its specified duties. Washington sided with Hamilton, believing the bank would indeed benefit the country financially, a decision that deeply frustrated Jefferson.

The Birth of Political Parties: Federalists vs. Democratic-Republicans

The intensity of their disagreements, particularly over the national bank and federal power, catalyzed the formation of America’s first true political parties. Hamilton, along with his allies, coalesced into the Federalist Party, advocating for a strong central government, a national bank, tariffs, and a pro-business agenda.

Jefferson, alarmed by what he perceived as Hamilton's monarchical tendencies and the Federalists' expansion of federal power, rallied his own supporters. He founded the Democratic-Republican Party, championing states' rights, agrarianism, and a more limited federal government. To counter Hamilton's influence and propagate his own views, Jefferson even funded Philip Freneau’s National Gazette, a partisan newspaper that became a sharp critic of Hamilton and Federalist policies. This early media battle highlights how deeply entrenched their rivalry became, spilling over into public discourse and shaping public opinion.

The Compromise of 1790: A Moment of Pragmatism

Despite their fundamental ideological chasm, Hamilton and Jefferson weren't entirely incapable of reaching common ground, at least on occasion. One notable instance was the Compromise of 1790. This behind-the-scenes deal, brokered by Jefferson and James Madison, involved a crucial swap: Hamilton secured congressional approval for his controversial national bank and the federal assumption of state debts, while Jefferson obtained the relocation of the United States capital to a new, more southern location along the Potomac River, which would eventually become Washington D.C.

This compromise was a testament to the high stakes involved in shaping the young nation. For Jefferson, it was a practical maneuver to gain something significant for his vision of the republic, even if it meant reluctantly aiding a key part of Hamilton's financial plan. However, Jefferson later claimed he felt "tricked" by this deal, suggesting his ongoing mistrust of Hamilton and perhaps a regret over empowering a policy he fundamentally opposed.

Navigating Foreign Waters and Continued Frictions

Their differences also manifested in foreign policy, particularly concerning the French Revolution Wars. Both men initially urged President Washington to serve a second term in 1792, recognizing the need for stable leadership amidst growing domestic and international tensions. They also agreed on the importance of American neutrality in the European conflicts. However, their underlying sympathies differed: Jefferson leaned towards revolutionary France, while Hamilton favored closer ties with Great Britain, reflecting their broader philosophical alignments.

As the decade progressed, their personal and political jabs grew sharper. Jefferson retired from Washington's cabinet in 1794, but their rivalry continued from afar. When Jefferson ran for president in 1796, Federalists, often echoing Hamilton's sentiments, branded him a hypocrite. Jefferson, equally cutting, once referred to Hamilton as "our Buonaparte" when Hamilton commanded a large army during the quasi-war with France, implying Hamilton harbored dictatorial ambitions.

The peak of their intertwined political destinies arguably came during the contentious Election of 1800. In a surprising twist, Hamilton, despite his deep opposition to Jefferson's principles, supported Jefferson over Aaron Burr, whom he considered a far more dangerous and unprincipled figure. Hamilton's influence, though not enough to swing the election directly, played a role in guiding Federalist votes, ultimately helping to ensure Jefferson's victory. This act, while tactical, underscored a complex reality: for all their enmity, Hamilton sometimes prioritized national stability over personal or party triumph, especially when confronting what he saw as a greater threat.

Remarkably, after Hamilton's tragic death in a duel with Burr, Jefferson spoke favorably of him, acknowledging his talents and contributions. This post-mortem recognition suggests that beneath the layers of political warfare, there was perhaps a grudging respect, or at least an understanding of the immense stature of his lifelong rival.

Enduring Legacy: Shaping America's Future

Historians widely agree that the conflicts between Hamilton and Jefferson symbolized America's first decade and profoundly shaped its future trajectory. John Ferling, a prominent historian, asserts that they were arguably the most important figures in defining the early United States. Their debates over federal power, economic systems, and the role of the people continue to resonate in modern political discourse, with contemporary political parties often mirroring aspects of their early American conflicts.

Public perceptions of their rivalry have naturally shifted throughout American history, reflecting changing societal values and historical interpretations. For a long time, Jefferson was often seen as the democratic idealist, while Hamilton was viewed as an elitist. However, Hamilton: An American Musical (2015) notably reframed this narrative for a new generation. The musical portrayed Hamilton as a self-made man of the people, a pragmatic visionary, and Jefferson as a somewhat arrogant monarchist, contrasting common historical perceptions and sparking renewed interest in Hamilton's complex legacy. This artistic interpretation demonstrates how our understanding of these foundational relationships remains dynamic and open to re-evaluation.

Beyond the Cabinet: Hamilton's Personal Bonds and Speculations

While the political battlefield defined much of Hamilton's public life, his private world was also rich with significant relationships—some deeply affectionate, others tragically complex. These personal connections offer a more intimate glimpse into the man behind the formidable public figure.

The Enigmatic Friendship: Alexander Hamilton and John Laurens

One of the most fascinating and historically debated relationships in Alexander Hamilton's life was his intense friendship with John Laurens. They met in the spring of 1777 while both served on George Washington's staff during the Revolutionary War. Their bond was immediate and profound, characterized by deep affection and intellectual camaraderie.

After Laurens departed for South Carolina to support the Revolutionary cause, he and Hamilton exchanged a series of letters that, by modern standards, read as remarkably intimate. In April 1779, a 24-year-old Hamilton wrote to 23-year-old Laurens, stating, "I love you" and adding, with a touch of playful exasperation, "You should not have taken advantage of my sensibility to steal into my affections without my consent." Such expressions of intense feeling were not isolated; many letters exchanged between them contained similarly passionate effusions.

The content of these letters, portions of which Hamilton’s descendants reportedly attempted to conceal or redact, has naturally led some modern scholars and biographers to speculate about a sexual relationship between the two men, and possibly even including the Marquis de Lafayette, creating what Hamilton's grandson famously referred to as "the gay trio."

Pulitzer Prize-winning historian James T. Flexner acknowledged that Hamilton's "passionate effusions naturally raise 'questions concerning homosexuality' in modern minds." However, Flexner also introduced crucial historical context. He pointed out that Laurens had a young bride in England, and Hamilton himself married Eliza Schuyler in 1780. Flexner ultimately concluded that "the essential data are lacking" to confirm a physical relationship. He further emphasized that "no one at the time sensed anything to whisper about," as homosexuality was not a prominent public issue or even a clearly defined social category in the 18th century as it is today.

The most widely accepted historical interpretation suggests that these young men, thrust into the crucible of war, developed incredibly strong, intimate bonds of affection, expressed through the highly sentimental and effusive writing style prevalent in the late 18th century. Such language, while striking to contemporary readers, was not necessarily indicative of a sexual relationship at the time. It reflected a culture where intense platonic friendships, particularly among men in stressful environments, could be articulated with a passionate vocabulary.

Tragically, John Laurens was killed in battle on August 27, 1782, near the Combahee River in South Carolina, at the young age of 27, cutting short a friendship that clearly left a deep mark on Hamilton.

Family Ties: The Hamiltons at Home

Beyond the intense friendships and bitter rivalries, Alexander Hamilton's life was anchored by his family. In 1780, he married Elizabeth "Eliza" Schuyler, a member of a prominent New York family. Eliza was a devoted wife, a steadfast partner, and a mother to their eight children. Their marriage, though not without its public challenges due to Hamilton's extramarital affair with Maria Reynolds, was ultimately a partnership of profound loyalty and affection, especially on Eliza's part. She meticulously preserved his legacy after his death, ensuring his papers were organized and his story told.

His children were also a significant part of his life, though often overshadowed by his public duties. His eldest daughter, Learn more about Angelica Hamilton, shared a particularly close bond with her father, and her later mental decline was a source of great sorrow for him. Hamilton was a dedicated, if often absent, father who deeply cared for his children's welfare and education.

These personal relationships, though sometimes less chronicled than his political battles, provide essential context for understanding Hamilton as a complete person, driven by both public ambition and private affections.

Understanding the Nuance: Why These Relationships Matter

Looking back at the relationship with Alexander Hamilton, whether it's his seismic rivalry with Jefferson or his deeply personal bond with Laurens, isn't just about dissecting the past. It's about drawing lessons that continue to inform our present.

Lessons from Fierce Political Rivalries

Hamilton and Jefferson's dynamic offers a powerful case study in the origins of political polarization. Their disagreements weren't superficial; they stemmed from genuinely different visions for the nation, each rooted in deeply held philosophical beliefs.

- Ideology vs. Personality: While their conflict often devolved into personal attacks, its core was ideological. They represented two distinct paths for American development: a centralized, industrial future versus a decentralized, agrarian one. Recognizing this helps us understand that political disagreements often reflect fundamental differences in values and priorities, not just personal animosities.

- The Power of Compromise (and its Limits): The Compromise of 1790 shows that even the most bitter rivals can find common ground when the stakes are high enough. However, Jefferson's later feeling of being "tricked" also illustrates that compromise doesn't always erase underlying tensions or regret.

- Defining a Nation: Their rivalry, far from being destructive, actually helped define the American political landscape. By articulating and championing their opposing viewpoints, they forced a robust debate that helped clarify the issues and set precedents for how a diverse republic would govern itself.

The Human Element in History

Hamilton's relationship with John Laurens, and the historical discussion surrounding it, reminds us to approach history with empathy and a nuanced understanding of past social norms.

- Context is Key: What might seem unequivocally one way in modern terms (e.g., "gay") needs to be carefully contextualized within the social, linguistic, and cultural frameworks of the 18th century. Words, gestures, and expressions of affection held different meanings than they do today.

- The Unknowable: Sometimes, the "essential data are lacking," as Flexner noted. Not every historical question has a definitive answer, and it's important to acknowledge these limits without projecting modern sensibilities onto the past.

- The Power of Friendship: Regardless of modern interpretations, the bond between Hamilton and Laurens was clearly one of deep mutual affection and support, forged in the crucible of war. It highlights the profound importance of human connection, even in the most challenging times.

Common Questions and Misconceptions About Hamilton's Relationships

History is often simplified, leading to persistent questions and misunderstandings. Here's a look at some common queries regarding Alexander Hamilton's relationships:

Was Alexander Hamilton Gay?

While Alexander Hamilton exchanged deeply affectionate letters with John Laurens, which some modern historians interpret as evidence of a homosexual relationship, there is no definitive historical proof of a physical sexual relationship. Historians like James T. Flexner emphasize that such expressions of intense affection were more common in 18th-century male friendships, and that the concept of "homosexuality" as a public identity or issue did not exist as it does today. Hamilton also married Eliza Schuyler and had children. The prevailing scholarly view is that their bond was an exceptionally strong, possibly romantic (in a broader, non-sexual sense), but ultimately platonic friendship, though the question remains open to interpretation and debate.

Did Hamilton and Jefferson Ever Get Along?

Hamilton and Jefferson largely did not get along, certainly not in a friendly sense. Their relationship was characterized by deep ideological opposition and political rivalry, often bordering on personal animosity. They disagreed fundamentally on the nature of government, economic policy, and foreign relations. While they did, on occasion, engage in political compromise (like the Compromise of 1790) or cooperate on specific issues (like urging Washington to serve a second term), these instances were born of pragmatic necessity rather than genuine camaraderie. Their conflict was the defining political battle of their era.

How Did Hamilton's Rivalry with Jefferson Shape America?

Hamilton's rivalry with Jefferson profoundly shaped America by laying the groundwork for its first political parties and defining the fundamental debates that would continue for centuries. Their clashes over federal power, states' rights, the national bank, economic development (commerce vs. agriculture), and foreign policy established the core ideological divisions that persist in American politics today. They essentially forced the young nation to confront and articulate its identity, leading to the creation of a system built on checks, balances, and competing visions.

Embracing the Complexity of Historical Figures

The relationships with Alexander Hamilton, particularly his defining rivalry with Thomas Jefferson and his intimate friendship with John Laurens, offer a vivid tapestry of human connection, ambition, and ideological struggle. They show us that the great figures of history were not monolithic statues, but complex individuals driven by a mix of public duty, personal affection, and unwavering conviction.

Understanding these relationships allows us to appreciate the dynamic, often messy, process by which the United States was forged. It encourages us to look beyond simplistic narratives and delve into the nuance, recognizing that even fierce rivals can, intentionally or unintentionally, contribute to the greater good. By engaging with these historical bonds, you gain a deeper appreciation for the human drama that underpins the very foundations of American democracy.